|

|

||

|

This 2001 photo shows the New Hampshire Turnpike (I-95) looking north from the South Road overpass in North Hampton. Expansion during the mid-1970s brought a new four-lane carriageway and a wide grass median. (Photo by Alexander Svirsky.) |

||

|

Length: |

||

|

16.2 miles (26.1 kilometers) |

||

|

Cash / Non-NH EZ-Pass: |

||

|

$2.00 (both directions) |

||

|

|

||

|

EARLY PLANS FOR A SEACOAST BYPASS: The first plan for a highway bypass along the New Hampshire Seacoast region was developed as early as 1933. At that time, traffic was beginning to choke two-lane US 1 (Lafayette Road) and two-lane US 1 NH 1A (Ocean Boulevard) through the towns of Seabrook, Hampton, Rye, and Portsmouth. Congestion was particularly acute during the summer tourism and winter holiday seasons. |

||

|

Newspaper reports circulated that the state wanted to route the highway through the marshes west of the town centers, effectively removing most traffic between Massachusetts and Maine from local roads. One local newspaper, The Hampton Union, commented in its editorial pages that the loss of traffic would cut local business by 30 percent, and offered a compromise solution of widening the existing US 1 to four (or even six) lanes. Businesses in the affected towns promptly signed the petition against the western bypass, and offered their own compromise solution of constructing a new section of NH 1A through Hampton west of Ashworth Avenue. |

||

|

Local businesses renewed their fight against the turnpike, and estimated that the construction of the highway (and the concomitant loss of traffic on US 1) would result in the loss of $80,000 per year in gasoline taxes, and $500,000 per year in lost wages. They also protested the limited number of exits on the proposed turnpike. Area residents joined the fight, fearing that they might not get compensated fairly for their properties. Despite heated opposition at public hearings, the State Legislature passed a $7.5 million toll road bill on the last day of the 1947 legislative session. The governor signed the bill into law in early 1948. |

||

|

BUILDING THE TURNPIKE: The 14-mile-long, four-lane turnpike, which was to be the first superhighway in the state, was to extend from the Massachusetts-New Hampshire border north to the Portsmouth traffic circle. A connection to the US 1 Bypass directed motorists to the southern terminus of the Maine Turnpike via the Maine-New Hampshire (Lift) Bridge. Reflecting pre-Interstate standards, the original turnpike featured grade separation and wide separation of interchanges, but limited shoulders and a simple steel median guardrail were among the turnpike's many shortcomings. A six-lane mainline toll plaza and separate exit tolls were built in Hampton. The turnpike was named a "Blue Star Memorial Highway" in honor of the state's World War II dead. |

||

|

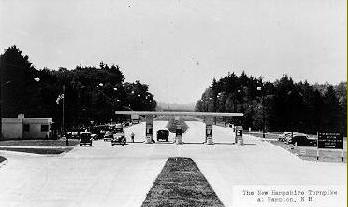

This 1950 photo shows the early days of the New Hampshire Turnpike (before it was known as I-95) at the Hampton toll plaza. When the NHDOT doubled turnpike capacity during the 1970s, it also rebuilt the Hampton toll plaza. (Photo by John M. Holman, from the Lane Memorial Library-Hampton archives.) |

||

|

A SMASHING SUCCESS: The New Hampshire Turnpike was built for an anticipated 1960 design capacity of 2,400 vehicles per day (AADT). Traffic volume reached this milestone only four years after the turnpike opened, and by 1960, when the I-95 designation was formally given to the New Hampshire Turnpike, the highway handled an average of 12,000 vehicles per day. The growth in traffic volume corresponded to the Seacoast region's evolution from a sparsely populated summer tourist community to a more populous, year-round suburban community. |

||

|

When the turnpike opened, traffic on US 1 dipped initially, but was back to pre-opening levels within a decade. Motorists soon took to alternative routes to avoid congestion on I-95, and this in turn led to increasing traffic on US 1 and NH 1A. By 1963, the Seacoast Regional Development Association complained to state officials that the traffic situation on US 1 was endangering the local economy. |

||

|

This 2016 photo shows the northbound New Hampshire Turnpike (I-95) approaching EXIT 4 (NH 16 and US 4 / Spaulding Turnpike) and EXIT 5 (US 1 Bypass; right exit) in Portsmouth. Before the Piscataqua River Bridge was completed in 1972, the Portsmouth traffic circle -- which this interchange bypasses -- served as the northern terminus of the turnpike. (Photo by Steve Anderson.) |

||

|

THE TURNPIKE TODAY: According to the NHDOT, the New Hampshire Turnpike carries approximately 55,000 vehicles each day (AADT), a figure that could nearly double on summer weekends. The turnpike received its one billionth vehicle in 1989, and only nine years later received its two billionth vehicle; it since has received its three billion vehicle. The speed limit on the turnpike has been 65 MPH since 1987. |

||

|

In the summers of 2003 and 2004, the NHDOT experimented with one-way tolls in the northbound direction at the Hampton toll plaza, leaving the southbound direction toll-free. There were ten northbound lanes (where a double toll of $2 was paid) and four southbound lanes (where traffic passed through at 20 MPH) during the experiment. Governor Craig Benson favored making the one-way tolls permanent, but local officials opposed the plan because they fear that congestion would worsen along northbound US 1. Amid annualized net losses of $180,000 and northbound traffic jams that stretched back into Massachusetts on I-95 and I-495, the NHDOT ceased the one-way roll experiment. |

||

|

This 2013 photo shows the New Hampshire Turnpike (I-95) at EXIT 7 (Market Street) in Portsmouth. This "free" section of I-95 was extended from the Portsmouth Traffic Circle to the Piscataqua River Bridge in 1972, the year the bridge was opened to traffic. (Photo by Alex Nitzman.) |

||

|

SOURCES: "Turnpike With Something Added" by Paul J. C. Friedlander, The New York Times (5/28/1950); "Hampton: A Century of Town and Beach (1888-1988)" by Peter Evans Randall, Town of Hampton (1989); "I-95 Toll Experiment Gives Free Ride One Way," The Exeter News-Letter (8/22/2003); "One-Way Tolls a Test of Patience" by Elizabeth Dinan, The Hampton Union (8/08/2004); "Two Ways To View I-95 Tolls" by Jerry Miller, The Manchester Union-Leader (9/05/2004); "NH Will Plug Into Electronic Tolls" by Electronic Tolls" by Christine McConville, The Boston Globe (1/09/2005); "Pay NH Your Toll, Respects" by Brian McGrory, The Boston Globe (6/11/2010); New Hampshire Department of Transportation; Lane Memorial Library; Josh Copeland; Dan Moraseski; Mike Moroney; C.C. Slater; Alexander Svirsky. |

||

|

NEW HAMPSHIRE TURNPIKE LINKS: |

||

|

NEW HAMPSHIRE TURNPIKE CURRENT TRAFFIC CONDITIONS: |

||

|

NEW HAMPSHIRE TURNPIKE VIDEO LINKS: |

||

|

THE EXITS OF METRO BOSTON: |

||

|

|

||

|

Back to The Roads of Metro Boston home page. |

||

|

Site contents © by Eastern Roads. This is not an official site run by a government agency. Recommendations provided on this site are strictly those of the author and contributors, not of any government or corporate entity. |

||